It’s just after 3pm on a Tuesday afternoon in Hackney and Richard Moore, Lionel Birnie and Daniel Friebe are looking for a bit of peace and quiet. The trouble is that around the busy East London streets of Broadway Market and London Fields school kids are heaving out onto the hot pavements and the nearby building sites that are sprouting up yet more flats in this trendy part of the capital are still in full swing. Add in the chatter of the many achingly cool characters lounging outside myriad cafés and coffee shops and, despite the lovely summer afternoon weather, things are looking, and most definitely sounding, pretty bleak.

Tag Archives: Tour de France

Climbs and Punishment – Book Review – Felix Lowe

For some reason books about epic cycle rides often struggle to maintain sight of the reason behind the particular journey. Caught up with geography, mileage and the inevitable misfortunes that happen along the way, we are quickly left to forget what the point of the epic ride was in the first place. Context is quickly abandoned in place of stories about encounters with mountains, deserts and (usually) wild coyotes or bears.

Happy Birthday – Eddy Merckx

Happy Birthday ‘Cannibal’

- TdF Winner – 1969, ’70, ‘ 71, ’72, ’74

- Giro d’Italia Winner – 1968, ’70, ‘ 72, ’73, ’74

- Vuelta a Espana Winner – 1973

- World Champion – 1967, ’71, ’74

- Paris-Roubaix Winner – 1968, ’70, ’73

- Milan-San Remo Winner – 1966, ’67, ’69, ’71, ’72, ’75, ’76

- Winner at Tour of Flanders, Liege-Bastogne-Liege, Flèche Wallone, Giro di Lombardia

- World Hour Record 1972

A uncompromising winning machine, Eddy Merckx bestrides professional cycling as an unassailable colossus. His palmares is without compare, his dedication to victory without parallel. Quite simply The Greatest of All Time, Merckx has no match; modern, historical or contemporary. On every surface, in every season, over every distance, across every parcours, Eddy was, is and will always remain the man to beat.

Yorkshire’s Grand Depart – Interview with Head of Media – Andy Denton

With the Tour de France less than a month away, all cycling eyes are turning to Yorkshire as final preparations are made before some of England’s most green and pleasant land is turned yellow for the couple of crazy days that will be Le Grand Depart.

Leading the team charged with communicating the story of Yorkshire’s time in the spotlight is Head of Media, Andy Denton. The Jersey Pocket caught up with this Kentish Lad who found his home in the Yorkshire Dales and then helped win the bid to bring Froome, Nibali, Contador and everyone else to England’s largest county.

The Complete Book of the Tour De France – Feargal McKay – Book Review

COMPETITION TO WIN A COPY AT THE BOTTOM OF THE PAGE..

As a self-confessed trivia and fact addict, one of my very favourite books as a teenager was Pears’ Cyclopedia. Not a particularly challenging text for an adolescent I will admit but, in pre-internet days, it was the single best source of a wide range of knowledge that I could lay my hands on. Being then of very limited means (variously pocket money, a paper round, a Saturday job as a kitchen porter, eventually a student loan) I tended to buy one every two to three years rather than each annual publishing. I was never disappointed by each new edition that somehow held a world’s worth of knowledge in a pocket-sized paperback. Looking back now from the considerably expanded knowledge base that we can call upon with just a few taps and swipes, it seems as quaintly antiquated as index cards or typewriters (both of which I also cherished at that time) but, judging by the goosebumps which prickled up and down my back earlier this week, the thrill of a receiving a book that portends to hold ‘all the answers’ creates the same feelings of excitement as it ever did.

Feargal McKay’s “The Complete Book of the Tour De France” (Aurum Press, £25 Hardcover) is by no means pocket-sized. Even in this pre-release paperback format it weighs something close to an Arenberg cobble and, in the new hardback edition that will be released on June 5th, it would probably do similar damage to a speeding front wheel*. But unlike the famed pave blocks that will define Stage 5 on this year’s Tour, this heavyweight cycling compendium can tell you everything you might ever want to know about the Grand Boucle. The old saying that “Knowledge is Power” certainly becomes more compelling when the source of knowledge that you are quoting from could also be used to knock your enemies senseless with a single blow. Try doing that with an iPhone…

The presentation of apparently endless facts about an annual bike race run in (roughly) the same format for over a century could ostensibly be a dull task to assemble and thereafter be an even duller task to read. Most encyclopaedia’s try to get around this issue by making sure there are a liberal amount of maps, diagrams and illustrations peppering the facts. Pears’ went a degree further by introducing a dozen or so ‘Special Topics’ to each edition. Sitting alongside the more usual Scientific, Historical and Geographical facts, these Special Topics brought some more subjective discussion and debate to the otherwise potentially mundane world of the almanac. More importantly they also delivered some context, personality and story to much of the rest of the book. In order to provide some context to the dry facts and figures that he has meticulously assembled, McKay has also wisely chosen to tell the stories behind the Tour’s various editions and developments, covering its scandals and glories in order provide a definitive statistical account of the Tour and the circumstances under which they were achieved.

And he has done it very well. McKay’s writing has an easy, conversational style that makes you imagine that you are listening to a learned friend telling you about each Tour. Knowing of his Irish background lends an accent to this imagined narration and the book, surprisingly for something that you had expected to be a simple compendium, quickly becomes more of a fireside Jackanory, to be consumed over many evenings, one chapter at a time. Time moves on but the roads and mountains remain and the wheels still turn to conquer them.

So, where to begin? Not necessarily at the beginning. McKay has naturally arranged his book in chronological order (and consumed that way the accompanying narratives would build to give a comprehensive – and comprehensible – understanding of the Tour’s progress through the decades) but one of the real joys of an almanac is that you don’t need to devour it in any particular order. In fact, there is a strong case for saying that you should never actually read it at all. Instead you should either consult it for a particular reason (just who was the Lanterne Rouge in 1937?) or you should just browse in order to allow it to reveal it’s secrets to you in a random, chance-like fashion by flipping pages until a word or name catches your eye. Anquetil, Aucouturier, Alpe D’Huez; Pottier, Pantani, Puy de Dome; Garin, Gimondi, Galibier… It’s an Aladdin’s Cave of Tour History, Tour Geography, Tour Science and Tour Politics. All you have to do is walk in..

The stories that you find next to the stats change as the motivating forces behind the Tour change from the requirements of marketing to requirements of politics, which in turn give way to commercialisation, which in turn give way to a need for regaining credibility. Throughout the main characters rise and fall as time takes it’s inevitable toll on all and yet the lists goes on. The charts at the end of each Tour story are presented in the same prosaic fashion throughout and, stripped bare of all the drama, intrigue and effort that the narrative has just given us, returns the riders to the immortality of the statistic. All are equal. Geants de la Route.

I would dearly love to see a future edition that included simple maps of each running of the Tour. Done in a consistent way, which was in keeping with the unchanging tables of Stage and Overall Winners, would not spoil the power of their simplicity but would add an extra dimension to the ‘Completeness’ of the book and would help chart the early decades of growth in particular. I don’t think the postmen around the country would thank me for adding an extra 50 or so pages to the already weighty volume but I think the cycling buffs (who will hugely enjoy this excellent book without them) definitely would.

Aurum Publishing are offering a free copy of The Complete Book of the Tour de France as a prize in the very first Jersey Pocket competition. Just send an email to thejerseypocket@gmail.com and a winner will be picked at random on June 5th.

* 02.06.14 update – Aurum have confirmed that the published book will be a paperback, not a hardback as initially intended.

Happy Birthday – Chris Froome

Happy Birthday Chris Froome

- TdF Winner – 2013

The shortest palmares so far in the birthday series but I don’t think we will be saying that in a few years time. Froome’s rise from the obscurity of racing in Kenya is a worthy backstory to what could be the biggest marquee in the pro ranks over the next decade. A relentlessly driven, relentlessly polite man, Froome seems to balance the fire and ice needed to be successful champion and a well-repected person.

Pantani:The Accidental Death of a Cyclist – Film Review

The new Marco Pantani film had its premiere in London’s West-End this week. I went along to see the film and also spoke with director James Erskine about it.

—

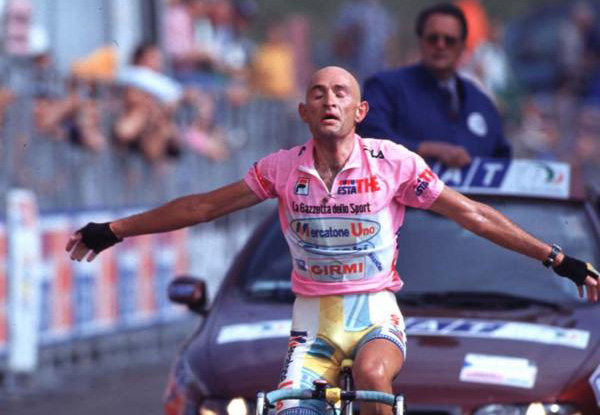

Often alone on the mountain climbs upon which he made his name. Ultimately alone in the Rimini hotel room where he died ten years ago, aged just 34. Always, it seems, alone in his own uncomfortable skin. For a man adored and feted throughout Italy for his cycling achievements and celebrated far further for his exhuberent verve in the saddle, Marco Pantani always remained a loner. Even when he was at the very centre of things – both good and bad – he somehow appeared detached. A riddle. An enigma. And that is what drew many of us to him.

James Erskine’s new film, Pantani: The Accidental Death of a Cyclist, makes no judgement upon the man known in turn as Little Marco, Elefantino and Il Pirata, and in the Q&A following the premiere in London on Wednesday night, the write-producer-director Erskine made no bones about that omission saying, “We wanted to make an emotional film and show the human cost.” he explained. In contrast to many recent cycling films, the director’s own presence is non-existent in the finished piece and the audience are allowed to make up their own minds as the whether he were ‘Pantani The Saint’, ‘Pantani The Sinner’ or someone struggling with both titles and wanting to be just Marco.

Life is much easier when our sporting heroes and villains are one-dimensional. “Four Legs Good. Two Legs Bad.” is easily modified into “1990’s Bad. 2010’s Good” but we all know how that black and white simplification played out in Orwell’s Animal Farm. Despite everything that has happened since Erskine started making his film 3 and half years ago, Lance Armstrong has managed to continue to polarise opinion, still loved and hated in equal amounts, but Pantani always walked a greyer line. Even before the film starts we bear witness to the truth. The BBFC certificate gives the film a 15 rating, pointedly noting that it includes “Drug Use, Injury Detail”. There you have it: in the most literal black and white. We know he cheated to win. So why do we feel differently about Pantani than we do about Riis, Ullrich, Virenque and Armstrong? Why is there always a question mark with Pantani’s legacy?

The very fact of his untimely death is obviously the key point in that it allows his sporting frauds to be viewed as part of a wider tragedy from which he could not ultimately be saved. Conspiracy theories crop up in the film about his fall from grace in ’99 – the pivotal moment in a career that had already been beset by disappointment and terrible injury – but they seem a side story to the main theme of a little boy lost in the world of men (a phrase which Erskine echoes in our conversation). An innocent. Such a thought would never occur about Riis, Ullrich or Armstrong who were as calculating as they come and who, in the case of Lance in particular, would seemingly stop at nothing to win. They all wanted to lead. Perhaps Pantani just wanted to be followed.

There is also a school of thought that suggests it was Pantani’s destiny to be deified and that the manner of his racing subliminally encouraged this. The repeated rises from the dead to claw back time in the mountain’s desert-like wastelands; the faithful disciples at Carrera who followed their messiah enmasse to the new team of Mercatone Uno; the outstretched arms crossing the winning line matching a crucifixion pose. His passing simply fulfilled this role as a tortured soul who struggled with greater highs and lows than those he conquered at the Galibier and Alpe d’Huez.

For just one moment in the film we see the anger of Pantani. A still frame of a grimace as he achieves another mountain-top win. For the only time there is fire in his eyes. All the other times, even when battling hard, the eyes are searching for something that is missing. When they close in ecstasy as he wins, he seems to have momentarily found it. But then it is gone again and he is still searching, and we must search with him, for an answer that cannot be found.

The film expertly assembles a remarkable amount of archive footage, talking heads, evocative scenery and subtle reconstruction. The archive material is suitably grainy in quality and breathless in it’s commentary and thus is superbly contrasted by the high-definition vistas of the silent Dolomite and Alpine ranges that punctuate the various sequences. The talking heads are superb with valuable input from Greg Lemond, Evgeny Berzin, Bradley Wiggins and Matt Rendell, whose book The Death of Marco Pantani was a key source for the film. It is Pantani’s family though, and his mother in particular, whose words will last longest in the memory. For all the scientific jargon and shots of blood-spinning centrifuges and syringes which dominate the central part of the film, it is her simple warmth and still raw sadness that touches deepest.

Marco Pantani wasn’t the de facto choice of subject when Erskine was first tempted into looking at making a film about cycling. “I’m intrigued by pain,” he says, speaking the day after the premiere from Belfast where he is finishing up his latest movie about the Northern Ireland football team taking on the Brazilians in the ’86 World Cup, “I’m interested in sportsmen absorbing pain and cycling seemed like a good place to look. The Individual versus themselves. A boxing film would have been too obvious.” James doesn’t count himself as a “proper cyclist”, though he watches it a bit and didn’t know of Pantani before being pointed in his direction by cyclist friends in the film industry. “I knew it would have to be someone from the Nineties for there to be enough of the sort of archive material I wanted and then someone suggested Pantani. I started with the obituaries, the English language books and videos. He was some who stood out from the pack. A maverick. Not a rebel but a maverick. Once we found Matt’s book I knew we had a story.”

Erskine tells the story in familiar fashion. The chronological history from birth to death is interwoven with the key achievements and events that defined the career. He likens the format to that of ‘Raging Bull’. We see the pirate conquering The Galibier in ’98 – all yellow wheels and saddle as he floats away in the rain. We see the empty victory atop the Ventoux ahead of Armstrong in 2000. Erskine uses a different filmic device to differentiate each significant win and to individualise them. Deployed partially to help the non-cycling audience they hope to attract and partially to give some texture to what might otherwise become a stylistic monotony of clips, I only noticed it for the first time during the Ventoux segment where I found the device chosen there a bit distracting. I asked James to explain the thinking behind this and highlight the other more subtle tricks they had used.

“We tried to give each segment a different feel to distinguish them. The ’94 Giro segment is quite straightforward but jumps around in time a little. It goes off and looks at something else and then comes back. We cut the ’99 Madonna di Campiglio sequence with whip-panned shots of trees. We were looking to take it faster and faster, punchier and punchier, higher and higher to give that final hallucinogenic moment before the fall.”

It’s the fall that defines the film of course; Pantani’s dramatic descent into cocaine addiction following his expulsion from the 1999 Giro d’Italia for a high haematocrit level when over 4 minutes in the lead. That is what Erskine felt showed the key elements of Pantani’s character, “He had an extreme psychology. There’s guilt, shame and huge insecurity about a two week ban that many others had at that time too. What mattered to me was why did Pantani take that series of false steps afterwards? Why did he start using cocaine, which increased his paranoia? What was it that took him over the edge when he could have come back just two weeks later and raced hard again? Why did he go bonkers? It was all really intriguing.”

Finding the answers were not so straightforward as asking them. It took a long time to get the family fully on board. “We spent a lot of time talking to them. Being considerate. It was difficult for them to think about EPO and cocaine – they are grieving parents – but they understood that it needed to show both sides of the story. We showed them the film before the press launch in Italy and they did have some issues but I think that ultimately they respect the work.”

The director also delayed the film’s release by a year to ensure that they had all the family material they needed and it was a wise choice given it’s importance in the finished article. The film has already been released in Italy and, despite falling well short of exonerating their saint, it received a warm welcome from the local partisan audiences. The main wonder was why it was a British team making the legacy film. In truth the film benefits from the distance and balance that Erskine gives it and it’s hard to imagine that coming from an Italian source.

Ned Boulting, who along with The Times’ cycling correspondent Jeremy Whittle admirably hosted the audience Q&A after the screening, said during his brief introduction before the film that this is ‘perhaps the greatest cycling story ever told’. Many, including myself, would take some exception with that but none would doubt that Pantani’s is the one of the great tales of modern cycling and after seeing the film I think that all would agree that here it has been expertly told.

Pantani: The Accidental Death of a Cyclist is released 16th May.|Visit Pantanifilm.com for details of screenings.

Happy Birthday – Bradley Wiggins

Happy Birthday Wiggo

- TdF Winner – 2012

- Quadruple Olympic Gold Medallist

- Six time track World Champion

Wiggins’ transition from Olympic track star to TdF winner, and his perceived gentlemanly attitude to racing, won him many French fans in 2012. Back in the UK he was loved for his unconventional podium speeches, his Mod style and for finally winning the Tour for Britain at the 99th edition. A supreme athlete when he focuses on a goal, he may yet have another career-defining moment up his sleeve.

Bonne Anniversaire – Louison Bobet

Happy Birthday Zonzon

- World Champion – 1954

- Tour de France Winner – 1953, ’54, ’55

- Paris-Roubaix – 1956

- Milan-San Remo – 1951

- Ronde van Vlaanderen- 1955

- Giro de Lombardia – 1951

France’s first post-war cycling hero, the elder and more successful of the two Bobet brothers was also the first rider to win the Tour de France three times in succession. His memory will be eternally wedded to the ‘Casse Desert’ section of the Col d’Izoard climb; a cruel, empty area of white rock and scree on the Southern approach, which he conquered twice to take the Maillot Jaune on route to overall victory.

Bonne Anniversaire – Henri Desgrange

Henri Desgrange – 31.01.1865 – 16.08.1940

- Hour Record – 1893

- Editor L’Auto newspaper – 1900 – 1940

- Creator of Le Tour de France – 1903

Desgrange is rightly seen as the father of the Tour. Latching onto an idea of one of his correspondents – Geo. Lefevre – to help boost circulation, he set his newspaper firmly behind the creation of what quickly became Le Grand Boucle. Famously harsh on the riders of the early years, he set the tone for the endeavour as one of grand ambition and epic suffering. His words make clear his thinking: “The ideal Tour would be a Tour in which only one rider survived the ordeal.”